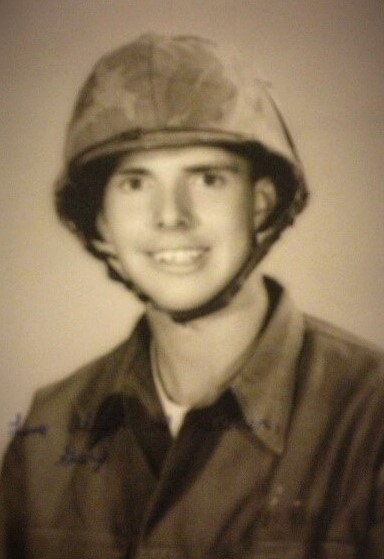

Image ID: A tattered armed forces of the United States ID Card showing a tealish-green border, eagle graphic, and Marine Corps text. A black and white picture of a young white male with dark hair is in the middle of the ID with the printed name Gary F. Baker, and Gary’s signature above that.

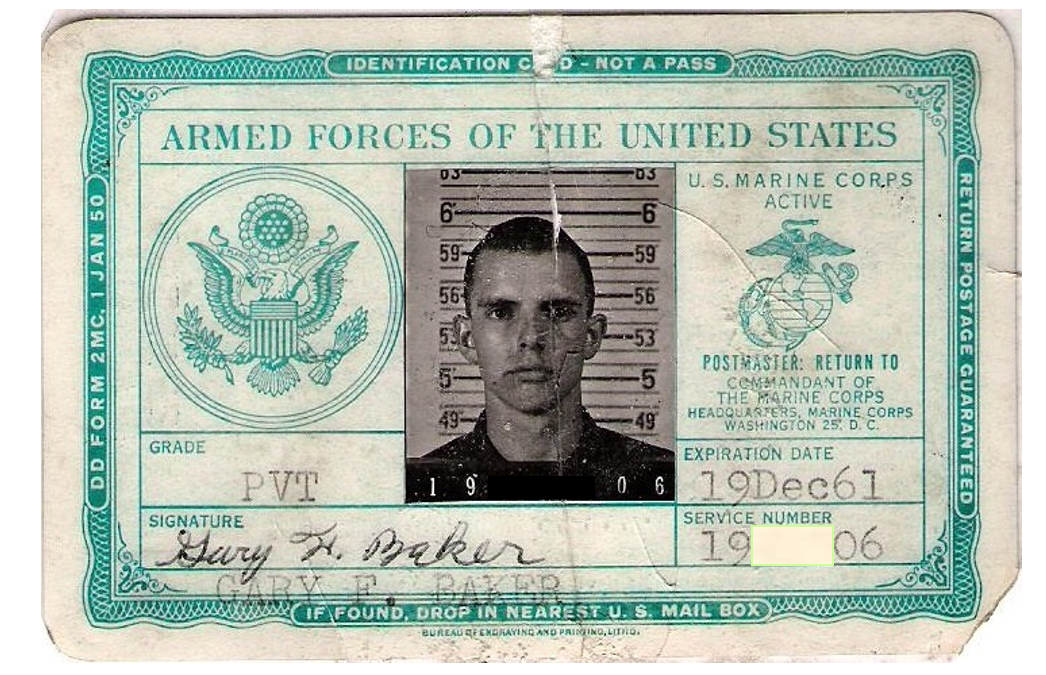

When my father died at the age of sixty-nine, in an alley in downtown Denver on August 5, 2013, the only things he had left to his name were the clothes on his back, his walker, the cell phone he used to call 911, and his military ID. He didn’t even have a wallet to keep it in. That had been stolen the week before. We asked the hospital (where they’d tried to save him) to donate his walker and clothes, and so, all we took home was the cell phone, and the military ID. A military ID with my father’s very young face staring back at us.

He was an abusive and hurtful man, my father. He was angry, addicted, and belligerent. Out of his five biological children, five step-children, and many grandchildren, and great grandchildren, only two of us were on speaking terms with him at the time of his death. I was not one of them. We were estranged, him and I.

He was a severely wounded man. A wounded man that wounded others.

Earlier this week, my mother and I attended a Veteran’s Day screening of Go in Peace, a film about soul wounds in veterans and how they manifest at end-of-life. It rang out loud and clear when Deborah Grassman, who works with dying veterans, said in the film, something along the lines of, “I don’t know what indoctrination the Marines use, but I know a Marine when I see one.”

I instantly thought of my father. My dad never saw combat. But, he’d joined the Marines at the age of seventeen. It was the early 1960’s, just before the U.S. entered the Vietnam War. The Marines were masters of breaking people, (children really) down, and building them back up to be hardened soldiers. War ready. Semper Fi.

Boot camp was weeks of hazing and beatings. There was plenty of trauma to be had just in those first few weeks alone. I’m certain that while my dad was likely already pre-disposed to having a fiery temperament, that his time in the Marines, war or no war, changed him. And, not in a good way. Indoctrination indeed.

Considering the veterans that did see combat – those that killed and maimed, and watched as their friends were maimed and killed – it’s no wonder that post-traumatic stress is a thing among vets.

On the heels of Veteran’s Day, where we spout things like HAPPY Veteran’s Day, and “thank you for your sacrifice,” we support veterans with our often superficial (though well-meaning) words, leaving a lot left unsaid. Just as there has been a lot left unsaid through much of many of these service peoples’ lives. Especially those of combat veterans.

The untold stories and soul wounds fester.

One of the post-film panelists, Greg Goettsch, talked about how he himself went decades without speaking about his time in the war. He rarely even identified himself as a veteran to others to avoid the conversation all together. A few years ago, when he decided that bottling it all up wasn’t serving him, he went looking for a program that supported veterans in telling their stories. Judgment free. He couldn’t find what he was looking for, so, he did something about it and founded the Qualified Listeners. Since its inception in 2017, the Qualified Listeners have reached six hundred people. Seventy-eight percent of them have been veterans. The rest were family members. The fact that over twenty percent of who they’ve heard from are family members, speaks to the impact that trauma and soul wounds have, not only on veterans themselves, but also on their families.

The film, by Karen van Vuuren, is an expose on how common it is for these suppressed traumas to surface when veterans are on their deathbed. Common themes include anger, shame, heightened anxiety, and the need for forgiveness. Given that these are common themes that may arise for anyone at end of life, certainly they may be that much more intense for veterans. I’ve heard family members say, about an otherwise gentlemanly type who’s lashed out at nurses and caregivers, things like, “that’s not my husband/father.”

Karen’s father, a Dutchman who was a child soldier in WWII, had soul wounds surface at the end of his life, and that was the catalyst for her to make this film. It is a documentary rich with insights into the very real challenges veterans may face, not only in life, but as death nears.

So, how do we support them, not only at end-of-life, but ideally in the here and now, years before death comes, to help mitigate the toll trauma is taking on them?

One thing we can do is listen to the untold stories.

Many veterans tell heroic stories. They have the “go-to” stories that they’ve shared over and over again. The ones they think people want to hear. The ones that are safe to tell. Stories of triumph and valor. And the hard stuff? Well, that gets buried. Deep down. Veterans carry the untold stories to protect themselves from reliving the traumas, and sometimes even more so, so that they can uphold their oaths to protect us.

I won’t lie, that hearing other peoples’ stories of trauma can be vicariously traumatizing. Meaning, just hearing the stories can be traumatic. Hence, why the stories go untold. Veterans know this. That being said, if you think you can ground yourself in non-judgment, and hold the space to hear the stories, what a gift that is to those that need to purge.

I want to be clear here, that it is not our job to go fishing for the untold stories. Veterans will share what they are willing to, when they are willing to, if they feel they are in a safe enough space to do so. The panelists shared that we can ask questions like, “I’m wondering if there’s anything from the war that may still be troubling you?” If they say no, don’t push. If they open up, follow up questions may simply be, “what else?” They will go as deep as they are willing to go. Remember, we are not trying to fix or reassure. Rather, we are witnessing, hearing, holding, and reflecting. A heartfelt “wow, that sounds like it was really scary for you,” or, “that must have been so hard,” can go a long way.

As much as we wish that we could rely on the VA, and professionals to hear, and to hold, the reality is that resources are spread thin, and many veterans don’t even qualify for VA benefits. We owe it to our veterans to not turn our backs. If you think you can answer the call, we invite you to do so.

If you are in Colorado, you may consider pointing folks towards the Qualified Listeners. The listeners are combat veterans who have been trained to listen.

“Have you ever tried to tell your story, your pain, your concerns to someone that hasn’t had the same or similar experiences? How can someone possibly understand if they’ve not stood in your shoes? We have. That’s what makes us qualified to listen to you.” –QL website

What a special program it is.

Greg offered another great example of how to open a conversation with a veteran, especially one that may down play their role in the military if they weren’t in combat, for example. By saying something like, “Some gave all. All gave some. Tell me about the some you gave?” that may be enough of an invitation. And, if not, that’s ok, too. We can’t force it. All we can do is extend the invite.

Deborah Grassman, from the film, founded Opus Peace. Opus Peace is a “non-profit organization whose mission is to provide educational programs to healthcare providers and others that help people reckon with the unassessed wounds of Soul Injury thereby liberating unmourned loss and unforgiven guilt/shame in order to restore personal peace…Learning how to grieve losses and learning how to forgive others and themselves for what they thought they should or should not have done became a liberating force that allowed the veterans in hospice to die healed.”

While, in my opinion, folks dying “healed” is a lofty goal, and “healed”/”healing” are loaded words/notions, the merits of wishing for healing understandable.

Though I didn’t catch who said it in the film (Dr. Ed Tick, or Deborah), I jotted down the sentiment that, “dying is fertile ground for healing.” The goal is to connect our veterans to services to heal trauma long before they die, but if it comes down to it, and they are facing the end-of-life, there is much we can do to help. And what that looks like, above all else, is opening our hearts, and lending an ear.

Dr. Ed Tick shared in the film, and Deborah echoed it on the panel, that we may not always be able to get very far with the healing process at end-of-life given that there may be so little time. Unfortunately, most people are connected with hospice for mere days, or weeks. Some may rarely be conscious when they arrive. What Ed likes to leave with the dying is that he will carry on their stories until their souls are at peace with how they’ve been honored, respected, and remembered.

Much love to those that work in end-of-life, that work with veterans, and those who are veterans, carrying soul wounds. Love to the families and friends effected by said wounds.

My father did not live a life of peace, nor did he go in peace. The same is true for countless others.

May we all show up, in any little ways we can, to try to make a difference in the lives, and deaths, of those on a similar path.

Many thanks to Karen for this film, and all her work in the death sphere.

http://goinpeacefilm.org/buy-or-rent/

http://www.qualifiedlisteners.org/what-we-do/

https://opuspeace.org/Opus-Peace/About.aspx

Gary F. Baker

12/01/1943 – 08/05/2013

Image ID: A sepia toned photo shows a young, clean shaven white male wearing military shirt and camoflagged helmet and smiling.

A very moving and informative item…