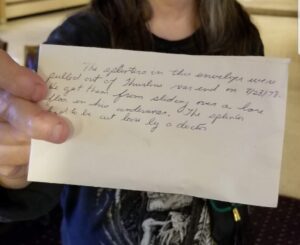

***Content Warning: There’s one heartfelt photo of Robert at his home funeral below.***

“His heart is mush…He’s going to pass.”

Those words will forever be seared into my mind. Words that flashed onto the screen of my work computer as I received play-by-play updates from my mother about my big brother Robert’s surgery.

The all too familiar moment of panic upon hearing this type of news set in. What do I do?

What. Do. I. Do?

I sobbed at my desk, visibly shaken and unable to think about next steps. Some coworkers came to the rescue. One offered to drive my car home while the other took me in hers. As we neared the parking lot, my mom called. I answered and heard nothing.

“Mom? Mom? Are you there? MOM?!”

My phone had bluetoothed to my vehicle while my hapless and helpless colleague sat inside listening to my mama’s wails.

It was a Thursday in Denver and I was supposed to have a biology midterm that afternoon. My 70+ year old mom had caught a Greyhound bus down to Oklahoma, adamant that she would not pack anything black. It was the fourth time she’d wring her hands while her second-born son underwent open heart surgery. First when he was 7, then again at ages 11, and 13. Now, he was 51, and the risk of his valve replacement was high.

A week prior, mom and I had gone to see a Pink Floyd cover band play at Red Rocks and I debated having the conversation. The conversation about what we would do if he died. It was supposed to be a celebratory night. A fun night. But, I knew. I knew I should at least mention it, and that I might as well get it out of the way as soon as possible.

As we drove through the rolling hills, and with my sunglasses hiding the tears that welled, I spoke.

“Mom, if Robert dies, please let me come to you. Don’t let the hospital rush you into calling a funeral home.”

That night, as the band played Time, a cool breeze kissed the salty tears streaming down my face. I sang with an amphitheater full of people, from deep within. “Shorter of breath, and one day closer to death.”

My brother IS going to die, I thought. If not next week, then someday. They all are. We all are. Damn it if I didn’t try to be optimistic, though. He wasn’t gonna die, yet, and I couldn’t miss my midterm.

I had just started pre-reqs in pursuit of a mortuary science program and was also in the middle of training to be a death doula. I needed to stay home. Mom would be okay. Robert would be okay. Everything would be…okay.

mom & i at the show

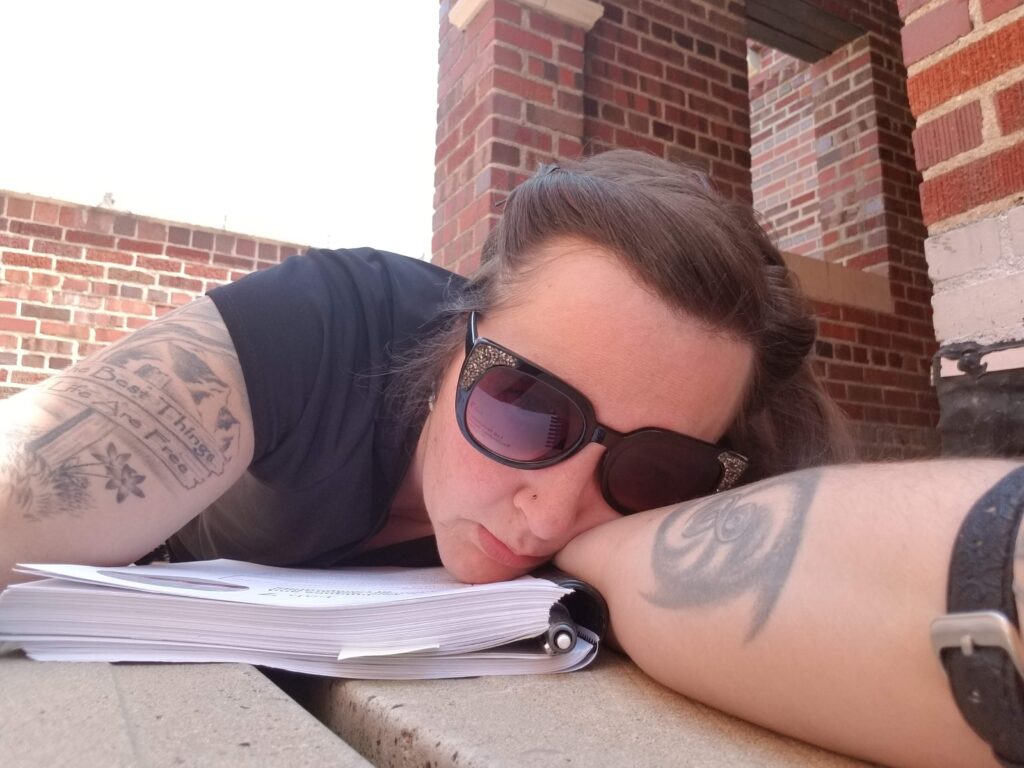

studying for the midterm

I gave her a card to take to him. It had a soaking-wet, sad-looking kitty on it. Robert loved cats. It read, “See, someone knows how you feel!” and I wrote some joke inside about giving the nurses hell. My intention was for it to be given to him after the surgery.

But, the morning of, when I asked my mom to go ahead and give it to him beforehand, she told me that she already had. The night prior.

It was eerily telling.

Regret is a common experience among bereaved humans. I regret not having talked to Robert by phone before he went under the knife that couldn’t even make it past his scar tissue. Before he never came back to us.

I just didn’t want it to sound like I was saying goodbye. So, I said nothing, (other than what was in the card which did include an “I love you,” at least).

Surgeons had put his surgery off for as long as they possibly could. The artificial aortic valve that had surprisingly lasted decades was failing. He would die without another replacement. But, they knew that he had a ton of scar tissue and were quite concerned about the outcome. Of the two surgeons he had, one was new, and one was a seasoned veteran. The newbie tried valiantly for hours to even get into Robert’s chest but it was impossible. His heart had essentially calcified to his breast bone. He was losing blood faster than transfusions could keep up. Hope was lost. The seasoned surgeon gently nudged the newer one to call it.

“We have to let this family start grieving.”

On the way home from work, in someone else’s car, I booked the next flight to Oklahoma City out of Denver leaving myself a very narrow window to get home, get packed, and get to the airport. Most of the clothes I threw into my luggage were dirty. This wasn’t supposed to happen.

The plan was for me to fly out while the rest of the family, my husband and dog included, would drive. The hubs dropped me off and as he pulled away I stood there, frozen. Thank goodness for the teddy bear of a man at the United kiosk who knew I needed help, and a hug. I hadn’t flown for eight years and I’d forgotten that my luggage was broken. I’d have to carry it.

Heavy on top of heavy.

I bought some airport-approved essential oils for bathing and anointing at some random kiosk. Then, I boarded my flight, and purchased the in-flight Wi-Fi. I needed to do some research into Oklahoma’s laws. I’d thought about doing it the week before, but hadn’t. As much of a planner as I am, it felt like I’d have been writing Robert off if I had.

airport frankincense

I’d known about home funerals for a few years at that point because I’d been quietly consuming content from the National Home Funeral Alliance, who has a state regulations webpage. What started out as me wanting to know more personally had grown into a fiery passion. I wanted to bring community deathcare awareness to my circles. I wanted to pivot into deathcare myself. In addition to my mortuary school pursuits I’d also enrolled in death doula training with what is now called the Conscious Dying Collective.

One of our assignments was to watch the home funeral documentary In The Parlour. I invited some of my fellow trainees over right before we were due to attend Phase II with our cohort. Right before my brother’s surgery. There is a scene in the film where a group of siblings adorn a banner with their hand prints and hang it from their sister’s coffin. I cried to the small group of women in my home about how I feared that this might be my sibling group’s truth mere days from then.

It was.

And to think, I had planned to invite my family over to watch the film.

We wouldn’t need a documentary to start a conversation about home funerals. We wouldn’t need a film to show us the value in community deathcare.

We lived it.

rental van space check

Upon landing I went to a rental lot to find a van fit for moving a body. Would I disclose to the clerk why I needed to see multiple vans, and why I was getting in to put down the seats and lay in the back of each one?

As I made my way to the hospital it was nearing dusk. They had moved my brother, who’d been dead for several hours, down to a bed in the emergency department. Mom had taken my directive not to let them rush her into calling a funeral home very seriously. And, honestly, the hospital was great.

I hadn’t even considered that Robert was a registered donor. LifeShare, Oklahoma’s organ procurement organization (OPO), kindly waited for me to arrive before they arranged the pick up of his body to recover corneas, tissue, and bone. We were still comfortably within their twelve hour postmortem window, so I sat and took some time with him.

At one point, after a shift change, a nurse making rounds came in to “check vitals.” She’d clearly missed the memo.

“Vitals on a dead guy?” I asked.

The color drained from her face and she was suddenly paler than Robert. After she’d apologetically backed out of the room (poor thing) my mother, living brother, and I laughed, and laughed, and laughed. So much so that mom’s coffee was spilling on the floor with each ha-ha-ha. What a welcome moment of levity that was (for us, anyway).

I shared with mom that my funeral director friend had kindly called some funeral homes for me while I was in flight. We’d been quoted $3500 for a two hour viewing and cremation. I’d only even humored the thought of using a funeral home’s space because Robert’s house was not going to be a good fit for a home funeral.

Where else would we have it?

Then, in walked Uncle Bob. Robert was Bob’s namesake. There this older gentleman stood in the hospital room with us when it dawned on me that we might have an option, after all.

“Bob, can we bring Robert’s body back to the farm to say our goodbyes?”

He didn’t hesitate at all.

“Of course. Robert loved the farm. The farm is home.”

It was a yes. We were doing it.

uncle bob with robert on the right and our brother billy on the left…bob died five months after robert

Robert went off to LifeShare that evening and we’d see him again sometime the next day at the farmhouse.

I made a solo trip the following morning to go find supplies. Three of my brothers (one dead, two living) and Bob, all resided in very small towns. I had to drive sixty-five miles one way just to find dry ice. I stocked up on that, and bought some absorbency pads, bed sheets, food, flowers, a fan, some candles, Kleenex, and a picture frame.

I wanted to print out and feature the last photo of Robert ever taken. He’s sitting in a wheelchair wearing his pre-op gown with a middle finger up. The bird he was givin’ was for our brother Jason who’d been teasing him about his newly cut beard. Robert was not happy to lose his length, as mandated by the surgeons. I love his shit-eatin’ grin in the photo! I know he was afraid. We all were. And, despite how itchy and annoyed about his beard trim he was, he was smiling.

When the photo dropped out of the store printer, warm in my hand, I couldn’t believe that he hadn’t even been gone a full 24 hours yet. I was already exhausted. I sobbed, in public, (again), musing about how the warmth in Robert had left by the time I’d arrived.

Back at the farm, I started to make a space. Uncle Bob had a nice sturdy folding table in his shed that would work just fine to hold my brother’s body. We draped it with sheets and a blanket, did a few other little things here and there, and then mom, Jason, and I drove from one small Oklahoma town to the next to gather up some things from Robert’s house. Car show trophies. Animal skulls. Bandanas. A hot rod supercharger. And, the flaming skull blanket that was hanging on his window.

I giggled at the hat-and-wig-wearin’ skeleton in the front seat of Robert’s truck as we left. He was known for riding around town with “Miss Bonie Maronie.”

robert pre-op giving the bird

miss bonie maronie

As we drove back to the farm, a lump sat large in my throat. I was nauseatingly anxious waiting for our person to be returned to us. Being confined and unable to move or “do” while in the car was tough. My mind raced. Can I really do this? Is this really happening? What will my family think? I hope I don’t screw it up!

We greeted one family member after another as they rolled in in waves from Colorado. LifeShare delivered Robert to us later that day in a plastic Unionall suit (I’ll be frank here) to prevent any leakage from his recovery sites, not to mention his premortem surgical incision. A couple of my brothers helped lift the gurney up the old farmhouse stairs, and we transferred his body onto the table.

My mother, sister, and I ritually washed the parts of his skin that were still exposed, and then we dressed him as a family. My sister cut his clothes up the back per my instruction. Jason put on his bandana.

Robert’s arms were stiff and kept falling out to the side hanging off the edge of the table, so I hooked his thumbs into his pants pockets to keep them in place.

Then came the ice.

I wrapped chunks of dry ice in brown paper bags and placed them, one under each of his shoulder blades, and one in the small of his back. I felt like I was winging it at that point. Keep the torso cool. That was my mission. It was the middle of summer in an unairconditioned farmhouse. We didn’t want things to go awry. I set up the fan I’d bought to keep air circulating, since dry ice offgases, and we were all set.

our baby sister kary kissing robert

For the rest of that day, and all of the next, we cried and laughed, laughed and cried. Each member of the family had the time and space to engage with Robert, or not. My husband, who at the time was vehemently opposed to seeing dead bodies, had driven there with one of my sisters and our dog in tow. I told him there was a room on the opposite side of the house where he could be if he didn’t want to see my brother. At every funeral we’d ever been to he never participated in viewings. So, I was shocked when he not only came into the room where we had Robert, but also got hands-on within minutes of arriving. I had to turn my brother’s body to place new dry ice underneath him and my man, who typically wouldn’t even look at the dead, jumped in to help. He was touching a decedent! A lot of that had to do with the fact that we were in a private space. He didn’t have a crowd of people watching him “perform.”

We were all free to joke, cry, cuss, hoot, and holler. Our terms. Our turf. No rush.

Two hours in a funeral home would never have been enough. Even just figuring out how to make that work with most of us arriving from out of town and needing to hit the road home again, all at different times, would have been tough.

Not to mention the added cost. We’d all just spent a ton on travel. This way, we’d only spent a couple hundred dollars on the supplies and food I’d procured, and we found a crematory back in the city that would only charge us $800.

We were grateful for the gift of time, and cost savings.

We wrote letters and placed them in Robert’s pockets. We had a dance party. Some of my siblings bickered about which of our dead relatives may have been the one to give him his “angel kiss,” which is what we called the little “smooch” mark of discoloration that had started to appear on his upper cheek bone on day two.

“It was Rupert!”

“No, it was Ruth!”

Uncle Bob would walk by on the way to and from his bedroom occasionally placing a hand on Robert’s chest saying, “I sure am gonna miss you.” Jason put feathers in Robert’s bandana. My sister Christy gathered rocks from the yard, washed them, and placed them on his body. My sister Kary’s three-year-old daughter tried to give him a sucker and was frustrated when he wouldn’t take it.

“I want him to wake up!” she stomped.

“We all do,” my sister said, softly.

We had plans for Robert to be picked up the next morning to be cremated. I had hoped for a (free) backyard burial, which is legal in Caddo County, but I inferred that mom wanted to keep Robert close, which she couldn’t do if he was buried states away, so cremation it was.

As I thought about his looming departure I realized something. This was the one and only time we’d all ever been in the same place at the same time because we’d been so spread out in age, and location.

My mom did not yet have a single photo with all seven of her children.

I asked if she wanted one, and she did. We lined up behind the table. Mom in the middle. Three living kids on each side. And her dead son in front of us all.

My eight-year-old nephew was learning how to do death by watching us. The last night Robert was with us I happened upon the little guy standing at the threshold of the room Robert was in. He was looking at an uncle he’d never met with sad, curious eyes. I noticed his mouth moving so I gave him some space to say what he needed to say, and when he was done, I approached him with a hug.

“I saw you talking to Uncle Robert, would you like to share what you said to him?”

“I told him I will miss him, and that I wish he was still alive.”

There were also a few times he’d walked by and hugged my mom asking, “How are you Nana?” and telling her that he loved her.

He may not have understood the magnitude of a mother losing a son, but he knew darn well that his Nana was hurting, and he cared.

our nephew in the threshold talking to robert

nana hugs

He’d cried a few times, but his rawest, sloppiest tears fell the morning he came to the farmhouse and Robert’s body was gone.

We’d let him know the night before to say goodbye because Robert was leaving in the morning, but it wasn’t until he saw the empty table that it hit him.

“I’ll miss him. I’ll miss him.”

Us too.

We had wrapped Robert in the blanket we’d draped the table with, helped him out of the house and into the transport vehicle, and watched as he drove away from us up the old dirt drive.

It was during my time there, on the farm, that I decided my mortuary school pursuits weren’t going to be a good fit for me, after all. I wanted to focus more on ritual and ceremony. I finished my doula training, found a celebrant program, and dove deeper into the world of home funerals, eventually joining the board of the National Home Funeral Alliance and co-authoring their Home Funeral Guidebook.

Here I am, seven years later crafting custom celebrations of life, leading community grief rituals, and teaching on a variety of topics in the death and grief sphere.

I’ve told Robert’s story, or parts of it, time and time again in various iterations. It’s been on podcasts and in magazines. There’s a snippet about our group photo in a New York Times piece, and the feature photo for that article is of our baby sister Kary kissing Robert’s cheek while he was laid out.

I’ve shared our story in community presentations, college death and dying courses, and coroners offices. I’ve featured it in my own workshops, and enrichment courses. I’ve talked about it in the bereaved sibling group I’ve facilitated for almost as many years as he’s been gone.

No matter how many times I tell it, even after all this time, it still hits hard.

My face may or may not be leaking as we speak.

As hard as it is to relive, and as hard as it can be to be in the death and grief sphere, I can’t imagine it any other way, now.

I’m not glad or grateful my brother died. But, I am grateful for the clarity that his death afforded me.

Community deathcare means everything to me. It’s deep-seated in my mortal marrow.

Robert’s home funeral was our first. It hasn’t been our only. And it won’t be our last.

If you’d like to learn more from me about community deathcare I’ve got an upcoming home funerals enrichment course in collaboration with the Conscious Dying Collective called The Art of What’s Possible: Exploring Home Funerals. I designed the art for the course, with a nod to Robert via the heart.

Rest easy brother.

You can also follow me on social media for future offerings, and there is a video testimonial at the bottom of my services page, if you’re interested.

course art by yours truly

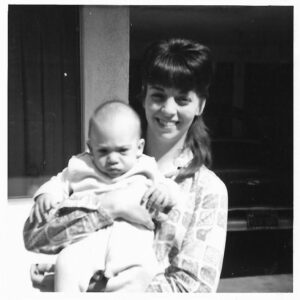

mom & baby robert

sock boobs

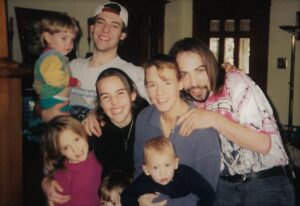

robert (far right) & fam

his kitty back in colorado laying on the framed photo of him

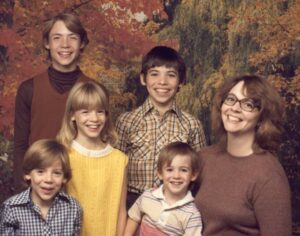

mom with her first five kids (robert’s standing in the middle just to her left)

me & robert

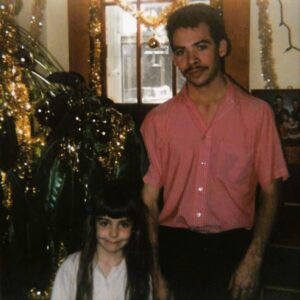

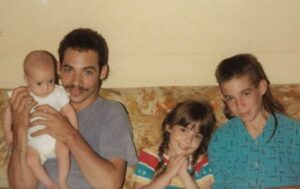

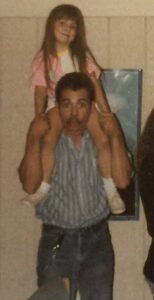

robert holding baby kary with tawnya & jason to their right

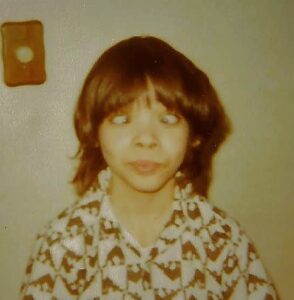

goof

the table robert was on, after he’d departed, displaying some of his skulls, leather jackets, trophies & more

splinter from robert’s ass

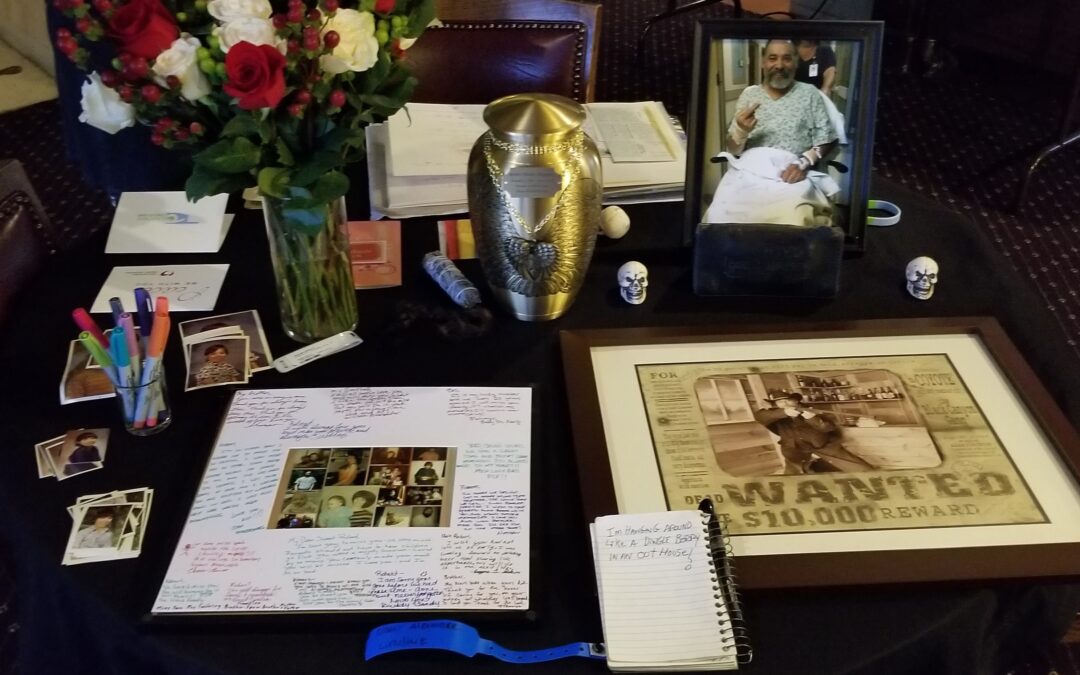

robert’s memorial in colorado with his urn

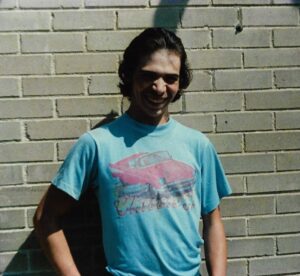

chevy shirt in ’87

me & robert

one of r’s skulls

my death doula graduation with one dead rose, & one living